I still remember the moment I saw the author list.

Second.

My name was second.

I did the analysis. Built the database. Wrote the first draft. Rewrote the third.

It was my first big study. I thought effort would speak for itself.

It didn’t.

Because I never discussed authorship upfront.

That’s how I learned: in research, credit is currency.

You don’t get what you deserve. You get what you negotiate.

And I’m not alone. One in two researchers has faced authorship disputes (Savchecko et al, 2024).

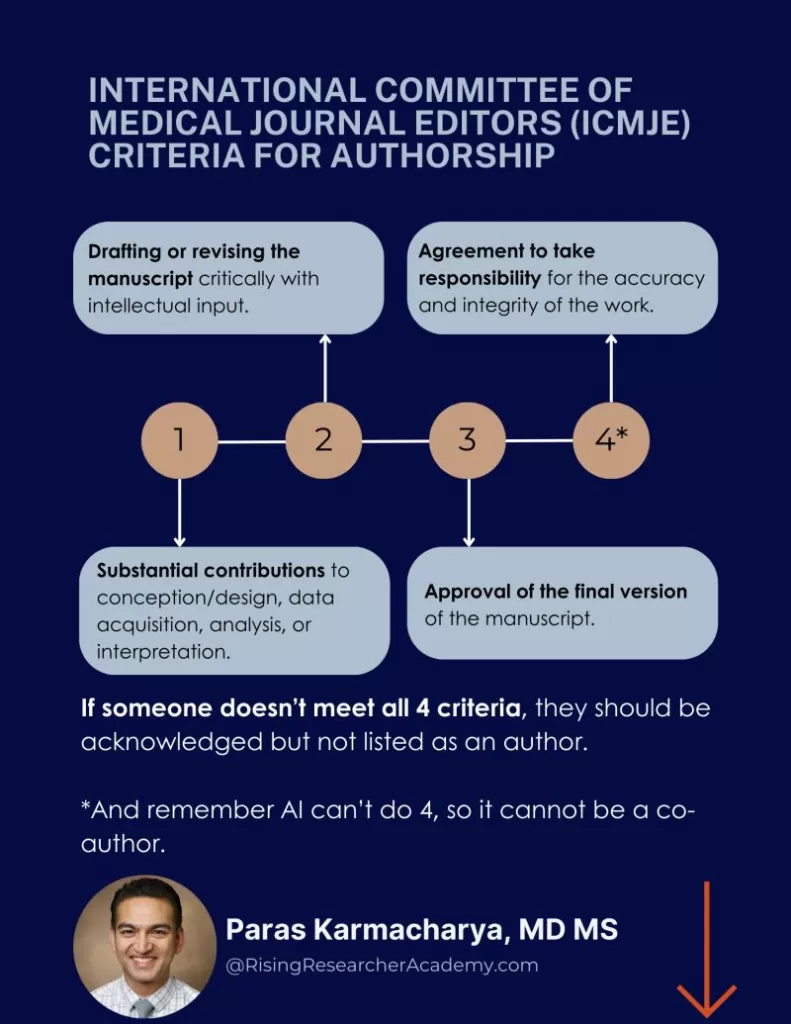

Who Should Qualify as an Author?

According to ICMJE guidelines, authorship requires:

- Substantial contributions to the design, data collection, or analysis

- Drafting or revising the manuscript

- Final approval of the version to be published

- Accountability for all aspects of the work

Sounds fair in theory.

But in practice?

I’ve seen senior faculty get second-author credit for reviewing a single paragraph. And junior researchers who did the actual work? Either buried in the middle—or left off altogether.

Let’s look at what each of those positions means in more detail.

What Authorship Really Means

Author order isn’t decorative—it’s strategic.

Each position signals something different. To hiring committees. To promotion panels. To grant reviewers. Here’s what they actually communicate:

✅ First Author – The one who did the heavy lifting. Data collection. Analysis. Drafting. Revising. This role can define your early career. I’ve seen trainees carry a study on their backs, only to be placed second “for optics.” If you led the work, speak up early. That spot matters.

✅ Middle Authors – Still valuable, especially near the top. But beyond the third or fourth position, visibility drops off. Truth is: unless your name is near the front or back, most people stop reading.

✅ Last Author – The anchor. Usually the senior PI, lab director, or mentor. This position signals leadership and vision. In multi-site studies, the fight for “who gets last” can be fiercer than “who gets first.”

✅ Corresponding Author – Often the senior or first author, but not always. This person handles communication with the journal. If that’s a role you want, clarify it early and never assume.

But even with these roles — Ambiguity lingers. Clarity is rare. Disputes are common.

That’s where objective tools like CRediT and authorship scorecards can help.

CRediT: Making Contributions Visible

The Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) was born out of a 2012 workshop hosted by Harvard and the Wellcome Trust—with input from ICMJE, Elsevier, and other stakeholders.

Instead of guessing who did what, CRediT breaks down authorship into 14 contribution roles:

| Contribution | Definition |

|---|---|

| Conceptualization | Developing research goals and aims |

| Methodology | Designing methods or creating models |

| Software | Coding, developing software or algorithms, testing components |

| Validation | Verifying results, ensuring reproducibility |

| Formal Analysis | Applying statistical, computational, or analytical techniques |

| Investigation | Conducting experiments or collecting data/evidence |

| Resources | Providing materials, equipment, datasets, or tools |

| Data Curation | Cleaning, annotating, and managing data for use and reuse |

| Writing – Original Draft | Writing the initial manuscript or substantial translation |

| Writing – Review & Editing | Revising, reviewing, or commenting on drafts |

| Visualization | Creating figures, tables, and data presentations |

| Supervision | Leading and mentoring research activities |

| Project Administration | Coordinating and managing the project |

| Funding Acquisition | Securing financial support for the project |

*Reproduced from Brand et al. (2015), Learned Publishing 28(2)

Each author can be credited for multiple roles, and it’s the corresponding author’s job to ensure contributions are discussed, agreed upon, and submitted correctly.

Many journals now require these statements—often published right before the acknowledgments. They don’t replace authorship criteria, but they clarify contributions in a way that the author order alone can’t.

Example CRediT statement:

PK, LJC, and AO were involved in the study conception and design. PK wrote the proposal and initial draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. PK is the overall guarantor.

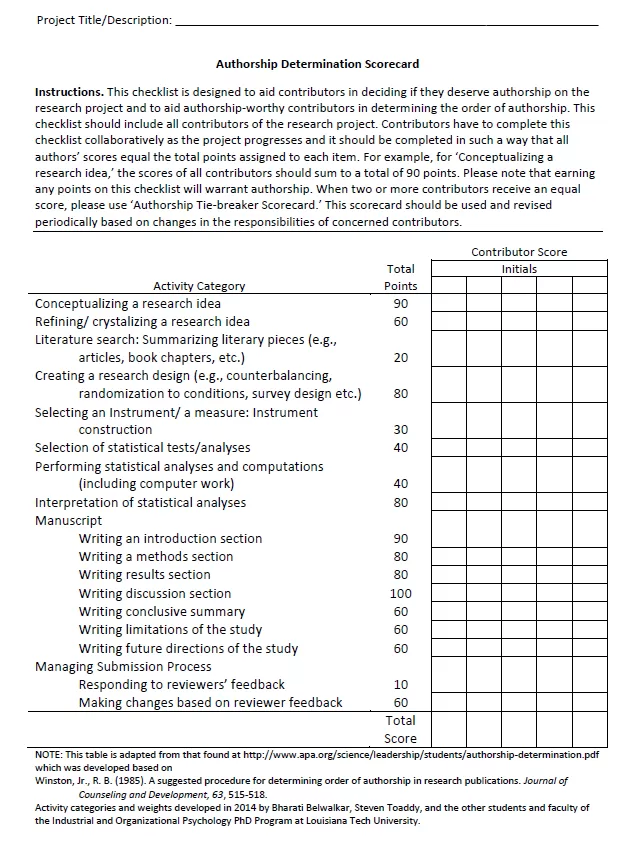

Authorship Scorecards: Structure Over Memory

In high-stakes or multi-author projects, assumptions don’t cut it.

That’s where a tool like the Authorship Determination Scorecard (based on work by Winston Jr., 1985) brings structure to the chaos.

Every task—study design, methods write-up, data analysis, revisions—is assigned a point value. Collaborators divvy up the points based on who did what.

It doesn’t make the decision for you. But it brings clarity and transparency when memories are fuzzy or tensions run high.

The goal isn’t perfection.

The goal is alignment.

When people see their contributions quantified, they feel seen.

And that builds trust.

What’s Not Okay

Let’s be explicit.

🚫 Gift Authorship – Adding someone for prestige, not contribution.

🚫 Ghost Authorship – Excluding those who did real work.

🚫 Honorary Authorship – Giving credit because someone “deserves a spot.”

🚫 Ambiguous Co-Author Roles – Co-first and co-senior authorship can help—but only when clarified upfront and in writing.

6 Ways to Handle Authorship Like a Pro

Taking all of the above into account, here’s how to take ownership—with clarity and fairness:

✅ 1. Start Authorship Conversations Early

Before the first chart is abstracted. Before the first R script is written.

Open the authorship discussion during project planning—not after the paper is drafted.

Pro Tip: Document expectations in a shared Google Doc or email. Who’s first, who’s last, who’s corresponding—get it in writing.

✅ 2. Use the CRediT Roles to Track Contributions

As the project unfolds, log each contributor’s roles using the CRediT taxonomy.

Pro Tip: Maintain a running sheet (Excel, Notion, Google Sheet) and update periodically. This is essential in long or multi-site studies.

✅ 3. Use a Scorecard for Multi-Author Projects

For large teams or high-stakes papers, a point-based scorecard (like the Winston method) may add objectivity.

Pro Tip: May be overkill in most cases. But can come in handy in high-stakes paper or multicenter studies where the roles are not so clear.

✅ 4. Know Your Target Journal’s Rules

Many journals now require CRediT statements or enforce ICMJE authorship criteria.

Pro Tip: Assign one person (typically the corresponding author) to cross-check journal policies before submission.

✅ 5. Acknowledge Non-Author Contributors

Not everyone belongs on the byline—but everyone deserves recognition.

Pro Tip: Keep a “thank you” log during the project. Add names to the acknowledgments early so you’re not scrambling at the end.

✅ 6. Revisit Authorship as Projects Evolve

If contributions shift, so should authorship.

Pro Tip: Reassess roles before the first full draft and again at submission. Use transparency as your default.

Authorship Is Advocacy

Publishing is essential.

But authorship?

That’s your fingerprint on the work.

It’s not just a name. It’s a record of your contribution. Your labor. Your stake in the science.

So speak up early. Track your effort. Align with your team.

Because when it comes to credit—assumptions are expensive.